I read the interesting article Asynchronous Methods for Deep Reinforcement Learning by the GoogleDeepMind group, and I’d like to share the insights I got from it.

The same group published the Deep Q-learning method to play Atari games with superhuman behavior some time ago.

Reinforcement Learning refresher

Let’s briefly review what reinforcement is, and what problems it tries to solve.

The general idea, is to have an agent that can interact in an environment by performing some action $a$. The effect of performing such action is to receive a reward $r$ and a new state $s’$, so that the cycle continues.

More formally we have:

- a discrete time indexed by $t$

- an environment $E$, made by a set of states ${s_t}$

- a set of actions ${a_t}$

- policy $\pi: s_t \longrightarrow a_t$, which describes what action should be taken in each state

- a reward $r_t$ given after each action is performed

At each time stamp $t$, the agent will try to maximize the future discounted reward defined as

where $\gamma \in [0,1]$ is the discount factor.

Please note that the previous sum is in reality a finite sum because we can assume that the episode will terminate at some point. In the case of Atari games, each game will terminate either with a win or loss.

Approaches to Reinforcement Learning

In general there are a few ways that we can use to attack the problem. We can divide them into the following categories:

- Value based: optimize some value function

- Policy based: optimize the policy function

- Model based: model the environment

The problem with modeling the environment is that each different problem (e.g. Atari game), will require a different model. Value and policy based methods are much more powerful (and interesting) because they don’t require any prior knowledge of the world they are trying to model. Note that this does not mean that the same (trained) model will be used with all the games. An agent that can play Breakout, is unable to play Pong and vice versa. The point I’m trying to make is that both of them can be trained using the same techique.

Value based: (Deep) Q-Learning

In this case we are tying to maximize the value function $Q$ defined as:

This function expresses the prediction of the future reward obtained by performing action $a_t$ in state $s_t$. While this is a nice and sensible mathematical definition, it does not give us any practical value, as that expected value is impossible to calculate in practice. There is a closed for for such equation, called the Bellman equation:

Now if we have a small number of states and actions, we could implement $Q$ as a matrix. It is possible to show that a random initialized matrix will converge to $Q$. In case of the Atari games, the number of state is untractable. Each state consists of 4 frames of the game (to give the direction of the ball), where each frame has $84x84$ pixels. Therefore the total number of states is:

and this assuming that each pixel is grayscale only!

Since the problem is very sparse (not all the possible combinations of states are possible), a deep neural network $Q=Q(s, a, w)$ was introduced to solve the problem.

In particular, the loss function is given by

Getting the best policy out of $Q$

Why is $Q$ useful? Given $Q$ is now easy to find the best policy for each state:

First let’s define $Q^*$, the optimal value function as

Which is the best value that we can get out of all possible actions.

For each state $s$ the action that maximizes the reward is given by

To recap, we just showed that if we are able to build $Q$ we will be in turn able to maximse the reward by select the best of all possible action.

Let’s look at the problem from the other point of view now: let’s start with the policy function and see how we can maximize it.

Policy based: Policy gradients

First of all we want to note that a policy can be either:

- deterministic, $a = \pi(s)$

- stochastic $\pi(a| s) = \mathbb P [a | s]$

In the first case, the same action is selected each time we are in the state $s$, while in the second case we have a distribution over all the possible states. What we really want is to to change such a distribution such that better actions are more probable and bad ones less likely.

First of all, let us introduce another function called Value function

Let’s spend one minute to fully understand what’s going on here.

Given a (stochastic) policy $\pi$ over all possible actions, $V$ is the expected value of the (discounted) future reward over all the possible actions. Or: what’s the average reward I will obtain in this state given my current policy?

As before, we can have a closed form for $V$, that will greatly simplify our life:

Side note, but important for the future: we can now rewrite $Q$ as:

Advantage function

If $Q$ represent the max value we could get from each state, and $V$ the average value, we can define the advantage function as

which is telling us how good is the action $a$ performed in state $s$ compared with the average. In particular

Policy gradients

Consider the quantity

where $\rho^{s_0}$ is a distribution of starting states.

$J$ is expressing how good a policy function is: it’s the expected reward of a policy weighted by a distribution of starting states.

We want to estimate the gradient of $J$ so we can make good policies (i.e. the ones with higher final reward) more likely.

Let’s now assume we are modeling $\pi$ with a deep neural networks with weights $w$, i.e. $\pi(a|s, w)$. Then the gradient of $J$ w.r.t. $w$ is

Actor critic model

Let’s look a the previous equation:

- $\nabla_w log \pi(a|s)$ is the actor, because it shows in which direction the (log) probability of taking action $a$ in state $s$ raises

- $A(s, a)$ is the critic: it’s scalar that tells us what’s the advantage of taking this action in this context (same action in different state will result in different rewards)

The only missing piece of the puzzle is $A%: how can we calculate it? Let’s get back to the definition:

Which means once we have $V$, we know $A$!

In real life the same neural network is approximating both the policy $\pi$ and the value function $V$ to give more stability and faster training. In fact they are trying to model the same underlying environment so a lot of the feature are shared.

Asynchronous

The last word of the title that we haven’t explained is the asynchronous one, but it’s also the easiest.

The idea is not new, and was proposed in the Gorila (General Reinforcement Learning Architecture) framework. It is very simple and effective:

- have several agents exploring the environment at the same time (each agent owns a copy of the full environment)

- give different starting policies so that the agents are not correlated

- after a while update the global state with the contributions of each agent and restart the process

The original Gorila idea was to leverage distributed systems, while in the DeepMind paper multiple cores from the same CPU are used. This comes with the advantage of saving time (and complexity) in moving data around.

Results and conclusions

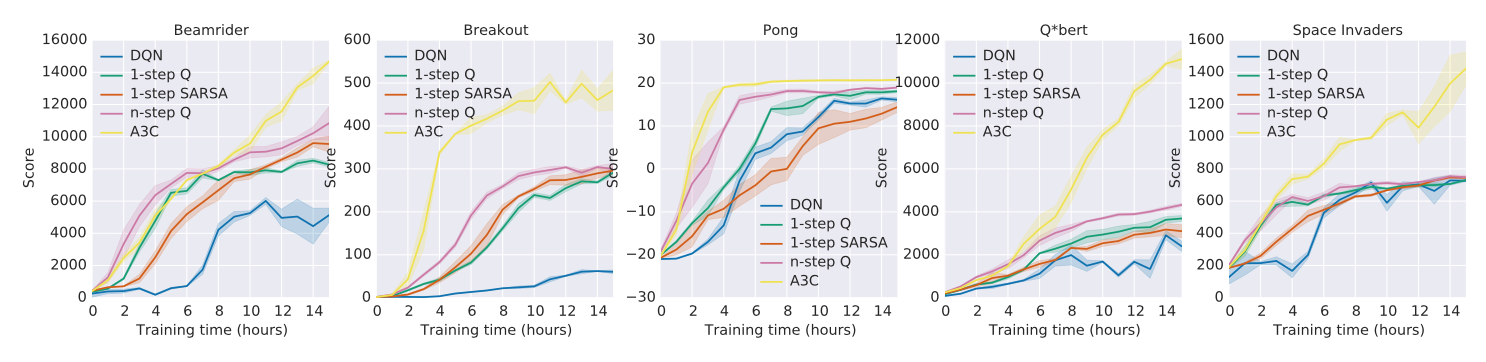

The results are impressive. By using just a 16 core CPU they are able to beat the state of the art of Deep Q-Learning and speed up training using the async trick.

This is the score for 5 different games as reported to the original paper.